Found in the Middle

Found in the Middle: Permutation Self-Consistency Improves Listwise Ranking in Large Language Models

Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized the field of natural language processing by demonstrating state-of-the-art performance across a variety of tasks. Among these tasks, listwise ranking—where items in a list are arranged based on relevance or importance—has gained particular attention in applications like search engines, recommendation systems, and document retrieval. However, LLMs often exhibit positional biases, where the order of items in the input list can affect the quality of the output ranking. This sensitivity can lead to inconsistent results and undermine the reliability of LLM-based ranking systems. To address this challenge, researchers have been exploring methods to improve ranking consistency and robustness against positional biases.

Research Gap

While existing methods attempt to mitigate positional biases in LLMs, most rely on either modifying the input prompt or introducing additional training, which may not be feasible for proprietary or black-box models. Furthermore, current approaches often fail to adequately address order dependence in listwise ranking tasks, where the performance of the model varies significantly with the input order. This limitation becomes more pronounced in real-world applications where input lists are inherently unordered, and the model’s output should be invariant to the order of input items. To bridge this gap, the proposed study introduces Permutation Self-Consistency (PSC), a novel method that aggregates rankings generated from multiple shuffled inputs to produce a final order-independent ranking, effectively reducing positional biases without requiring model fine-tuning.

Background

Kendall Tau Distance

The Kendall tau distance is a metric used to measure how different two rankings are by counting the number of pairwise disagreements between them. It is widely used in ranking tasks to evaluate how one ordering deviates from another. But, how it work?

Given two rankings, \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\), the Kendall tau distance is calculated as:

\[d_\kappa(\sigma_1, \sigma_2) = \text{Number of discordant pairs in } \sigma_1 \text{ and } \sigma_2\]- Discordant Pair: A pair of items \((i, j)\) is considered discordant if the relative ordering of \(i\) and \(j\) is different in \(\sigma_1\) and \(\sigma_2\). For example:

- In \(\sigma_1\), if \(i > j\) (item \(i\) is ranked higher than \(j\)).

- In \(\sigma_2\), if \(j > i\) (item \(j\) is ranked higher than \(i\)).

Let us have some examples: Consider two rankings of items \(A, B, C, D\):

- Ranking 1: \(\sigma_1 = [A, B, C, D]\)

- Ranking 2: \(\sigma_2 = [B, A, D, C]\)

- Compare pairs of items:

- \((A, B)\): \(A > B\) in \(\sigma_1\), \(B > A\) in \(\sigma_2\) → Discordant.

- \((A, C)\): \(A > C\) in both → Concordant.

- \((A, D)\): \(A > D\) in both → Concordant.

- \((B, C)\): \(B > C\) in \(\sigma_1\), \(C > B\) in \(\sigma_2\) → Discordant.

- \((B, D)\): \(B > D\) in \(\sigma_1\), \(D > B\) in \(\sigma_2\) → Discordant.

- \((C, D)\): \(C > D\) in \(\sigma_1\), \(D > C\) in \(\sigma_2\) → Discordant.

- Total Discordant Pairs: 4

But, why and how it can be useful?

- Quantifies Differences: The Kendall tau distance provides a precise way to measure the disagreement between rankings.

- Symmetry: \(d_\kappa(\sigma_1, \sigma_2) = d_\kappa(\sigma_2, \sigma_1)\), making it easy to compute regardless of the reference order.

Central Ranking

A central ranking is a single ranking that best represents the consensus of multiple rankings. It is found by minimizing the total Kendall tau distance between the central ranking and all the input rankings.

If we have \(m\) rankings \(\sigma_1, \sigma_2, \dots, \sigma_m\), the central ranking \(\sigma_\text{central}\) is defined as:

\[\sigma_\text{central} = \arg \min_{\sigma} \sum_{i=1}^m d_\kappa(\sigma, \sigma_i)\]This means \(\sigma_\text{central}\) is the ranking that has the smallest total pairwise distance (Kendall tau distance) to all the individual rankings.

But, why and how it can be useful?

- Consensus Representation: It summarizes multiple rankings into one, ensuring it reflects the “most agreed upon” ordering.

- Order Independence: By minimizing distances to all rankings, it is robust to biases or variations in individual rankings.

Let us have some examples. Suppose we have three rankings:

- Ranking 1: \(\sigma_1 = [A, B, C]\)

- Ranking 2: \(\sigma_2 = [B, C, A]\)

- Ranking 3: \(\sigma_3 = [C, A, B]\)

To find the central ranking:

- Compute Kendall tau distances between all possible rankings and the input rankings.

- The ranking that minimizes the total distance is the central ranking.

For this case, the central ranking might be \(B > C > A\), as it minimizes the pairwise disagreements with \(\sigma_1, \sigma_2, \sigma_3\).

Kemeny–Young Method

The Kemeny–Young method is a mathematical approach for finding the central ranking. It works by evaluating all possible rankings and selecting the one that minimizes the total Kendall tau distance to the input rankings. While this method is NP-hard (computationally expensive), efficient approximations can be used for practical cases. This method ensures that the final ranking reflects a robust consensus of all input rankings, reducing the impact of noise or biases in any single ranking.

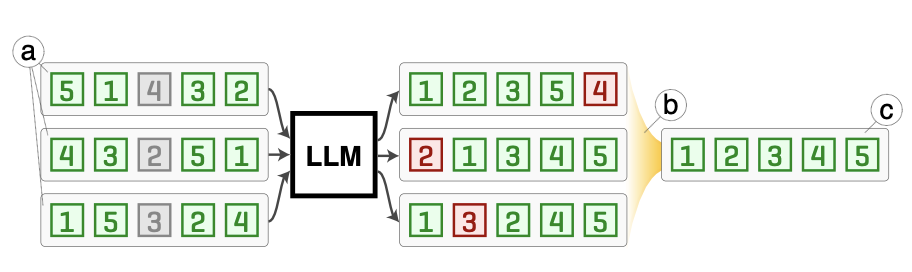

Solution: Permutation Self-Consistency (PSC)

To tackle positional biases in listwise ranking tasks, the authors propose Permutation Self-Consistency (PSC), a novel decoding strategy designed to improve ranking quality, consistency, and robustness to input order. The method leverages multiple shuffled versions of the input list, processes them independently through the language model, and then combines the outputs to produce a robust, order-independent ranking.

Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of their solution:

Step 1: Shuffle the Input List

The first step involves shuffling the input list multiple times. For instance, if the task is to rank passages based on relevance to a query, the list of passages is shuffled randomly \(m\) times (e.g., \(m = 20\)). Each shuffled version of the list is then passed through the LLM along with the same instructions.

- Why shuffle? Shuffling the input list introduces diverse orderings, ensuring that positional biases associated with any one specific order are averaged out during the aggregation phase.

- Example:

Original input: \([A, B, C]\)

Shuffles: \([B, A, C], [C, B, A], [A, C, B], \dots\)

Step 2: Generate Rankings for Each Shuffle

Each shuffled list is processed independently by the LLM to produce a ranked output. The LLM provides a ranking of items for each input order.

- Key Insight: The rankings generated for different shuffles may vary due to positional biases inherent in the model. Some shuffles may place undue importance on items appearing earlier or later in the list.

- Output Example:

For \([B, A, C]\), the LLM might rank items as \(A > C > B\).

For \([C, B, A]\), the LLM might output \(B > A > C\).

Step 3: Aggregate Rankings

To combine the rankings generated from all \(m\) shuffles, the method uses a robust aggregation strategy. Specifically, the authors employ the Kemeny–Young method, which finds the ranking that minimizes the total pairwise disagreements (measured using Kendall tau distance) with all the generated rankings.

- Kemeny–Young Aggregation:*

- Given \(m\) rankings, it identifies the central ranking that best represents the consensus.

- This ranking is the one that is closest to all \(m\) rankings in terms of Kendall tau distance, which measures how “out of order” one ranking is compared to another.

- Example: If the rankings from 3 shuffles are:

\(A > C > B\), \(B > A > C\), and \(C > A > B\),

the Kemeny–Young method would calculate the disagreements between all pairs of rankings and output the ranking \(A > B > C\) as the central consensus.

Step 4: Output the Final Ranking

The final step is to return the central ranking as the output. This ranking is:

- Order-independent: It does not depend on the specific order of the input list.

- Robust: Positional biases introduced by any single shuffle are averaged out through aggregation.

- Improved in quality: By leveraging multiple perspectives (shuffles), the final ranking better captures the relationships among items.

Why It Works

- Randomization Breaks Biases: Randomly shuffling the input list ensures that no single input order dominates the LLM’s behavior.

- Consensus Reduces Noise: Aggregating multiple rankings effectively marginalizes out positional biases, producing a more reliable final ranking.

- Order Independence: By considering all possible input orders (via shuffles), the method creates a ranking invariant to how the items were presented.

Efficiency Considerations

- Shuffles (\(m\)): The authors find that even a small number of shuffles (\(m = 5\) to \(10\)) significantly improves ranking quality, with diminishing returns for larger \(m\).

- Aggregation Cost: While exact Kemeny–Young aggregation is computationally expensive (\(O(n!)\)), the authors use efficient approximations (\(O(m^2 \cdot n^2)\)) to handle practical scenarios like 20 items and 20 shuffles.

This method is particularly effective for tasks like passage reranking, sentence ordering, and word sorting, where input lists are inherently unordered and positional biases can significantly impact results.

Experiments

The authors evaluate the effectiveness of PSC through experiments on sorting tasks and passage reranking tasks. These tasks demonstrate how PSC improves ranking performance and reduces positional biases.

1. Sorting Tasks

The authors use three synthetic datasets to evaluate PSC on tasks with inherently comparable items:

- MathSort: Sort arithmetic expressions by value.

- WordSort: Arrange words alphabetically.

- GSM8KSort: Order scrambled sentences from a reasoning dataset.

Setup

- Five LLMs are tested: GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and open-source models like LLaMA2 and Mistral.

- \(m = 20\) shuffled input lists are used for each example, and the results are aggregated with PSC.

Results

- PSC improves performance across all tasks and models, with significant gains for smaller models (e.g., LLaMA2-7B improved by 157% on MathSort).

- Even for powerful models like GPT-4, PSC yields moderate improvements (e.g., 2–7%).

- PSC consistently outperforms individual runs and standard inference methods by combining rankings from multiple permutations.

2. Passage Reranking Tasks

The authors assess PSC on real-world datasets:

- TREC Deep Learning Tracks (DL19 & DL20): Passage ranking datasets where passages are ranked by relevance to a query.

Setup

- Inputs include \(n = 20\) or \(n = 100\) passages.

- Models tested: GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and RankVicuna (an open-source fine-tuned model).

- PSC is compared against baseline methods like RankGPT and RankVicuna.

Results

- PSC consistently improves nDCG@10 scores (a ranking quality metric).

- For GPT-4, PSC boosts ranking performance by up to 5% relative to baseline methods.

- Smaller models (e.g., GPT-3.5) see smaller but meaningful improvements.

- The method achieves significant gains even with fewer shuffles (\(m = 5–10\)).

3. Positional Bias Analysis

The authors analyze how PSC mitigates positional biases by studying the impact of input order:

- Models like GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 exhibit positional biases (e.g., favoring items at the start or end of the list).

- PSC reduces these biases by averaging over multiple shuffled inputs, leading to fairer rankings.

Key Findings

- PSC works well across both synthetic and real-world ranking tasks.

- It provides larger gains for smaller models and more challenging tasks, where positional biases are more prominent.

- The method scales effectively with \(n = 20\) items and \(m = 20\) shuffles, balancing quality improvements with computational cost.

These experiments demonstrate that PSC is a robust and practical method for improving ranking quality and mitigating positional biases in LLMs.

Conclusion

Permutation Self-Consistency (PSC) is a simple yet effective method for mitigating positional biases in listwise ranking tasks. By aggregating rankings from multiple shuffled inputs, PSC produces robust, order-independent results without requiring model fine-tuning. Experiments on both synthetic sorting tasks and real-world passage reranking datasets demonstrate significant improvements in ranking quality, particularly for smaller models and challenging scenarios. With its scalability and ability to work with black-box LLMs, PSC offers a practical solution for improving the fairness and consistency of ranking systems powered by large language models.