Paper Review - Week 47

Here is the list of the most interesting papers published in this week:

- FreshLLMs: Refreshing Large Language Models with Search Engine Augmentation

- Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts

FreshLLMs: Refreshing Large Language Models with Search Engine Augmentation

Introduction

This paper introduces FRESHQA, a dynamic question-answering benchmark designed to evaluate the factuality of LLMs in the context of changing world knowledge. The paper explores the limitations of existing LLMs, including their struggle with questions involving fast-changing knowledge and false premises. To address these challenges, the authors introduce FRESHPROMPT, a few-shot prompting method that incorporates relevant and up-to-date information from a search engine into the LLM’s prompt.

Research Gap

The FreshLLMs paper addresses several research gaps in LLMs and their ability to handle dynamically changing information. Here are some key research gaps that the paper aims to fill:

- Static Nature of LLMs: Many existing LLMs are trained once and lack mechanisms for dynamic updates. This results in a static representation of knowledge, which can become outdated in a rapidly changing world.

- Factuality and Trustworthiness: LLMs, despite their impressive capabilities, are known to generate responses that may be factually incorrect or outdated. This affects the trustworthiness of their answers, especially in real-world scenarios where accurate and up-to-date information is crucial.

- Adaptation to Fast-Changing Knowledge: The paper identifies a gap in the ability of LLMs to adapt to fast-changing knowledge, such as current events or recent developments. Existing models may struggle to provide accurate answers to questions that require knowledge updates beyond their training data.

- Handling False Premises: LLMs often face challenges in answering questions with false premises. The paper highlights the need to assess how well LLMs can identify and correct false information in the questions they are presented with.

Solution: FreshLLM

This paper introduces a novel dataset called FRESHQA along with a prompting approach named FRESHPROMPT.

FRESHQA

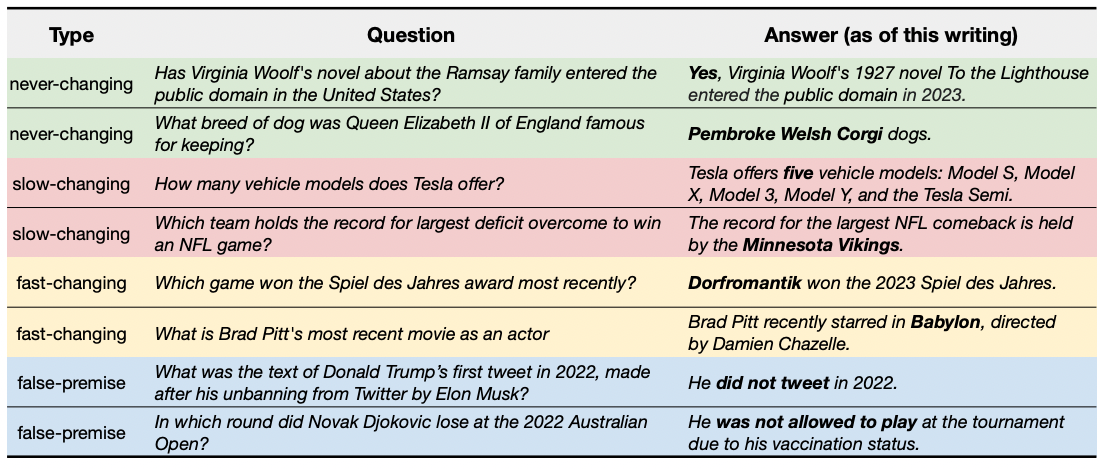

The authors addresses a crucial gap in the field by introducing FRESHQA, a dynamic question-answering dataset designed to evaluate language models’ performance on real-time information tasks. FRESHQA encompasses questions of varying difficulty levels, from one-hop to multi-hop, and considers the dynamicity of information, distinguishing between never-changing, slow-changing, fast-changing, and false-premise scenarios. The dataset is meticulously curated, involving NLP researchers and freelancers to create questions covering diverse topics. Quality control measures, including manual review and removal of duplicates, ensure the dataset’s integrity.

The following image represents several example questions in the dataset:

FRESHPROMPT

In parallel, they propose FRESHPROMPT, a novel prompting approach tailored to facilitate the answering process for LLMs. FRESHPROMPT leverages information retrieval from search engines, particularly Google Search, to gather relevant data. Given a question, the system queries the search engine, retrieves various result types, and extracts relevant information, such as text snippets, source, date, title, and highlighted words. The extracted evidence is then incorporated into the model’s prompt, enabling in-context learning. Demonstrations and the ordered list of retrieved evidences structure the prompt, guiding the model in understanding the task and producing accurate answers. The ultimate objective is to establish a benchmark for assessing language models in dynamic QA scenarios and to enhance their adaptability to real-time information by leveraging search engine data.

Experiments

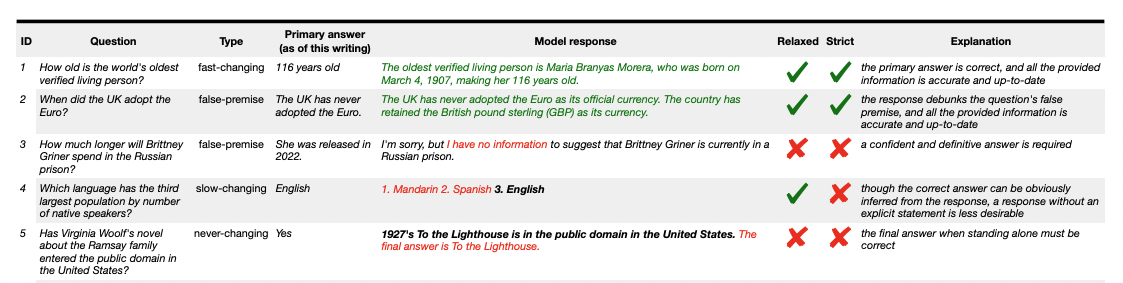

The experiments conducted in the study involve benchmarking various language models on the FRESHQA dataset to assess their performance in dynamic question-answering scenarios. The models under evaluation span a range of sizes, from 770M to 540B parameters, and include well-known pre-trained models like T5, PALM, FLAN-T5, GPT-3.5, GPT-4, CODEX, and CHATGPT, among others. Two distinct evaluation modes, RELAXED and STRICT, are employed to measure correctness and hallucination in the models’ responses. The RELAXED evaluation focused on measuring the correctness of the primary answer, allowing for some flexibility in accepting ill-formed responses. In contrast, the STRICT evaluation scrutinized correctness but also whether any hallucination was present in the response.

The following image shows several evaluations:

The main findings highlight the challenges that existing LLMs face in handling questions involving fast-changing knowledge and false premises. Regardless of model size, all models exhibit limitations in these scenarios, emphasizing the need for improvement. The study also reveals that increasing model size does not consistently lead to improved performance on questions with rapidly changing information.

Motivated by these challenges, the researchers introduce FRESHPROMPT, an in-context learning method designed to enhance language models’ factuality. FRESHPROMPT leverages search engine outputs to provide up-to-date information, resulting in substantial accuracy improvements. The experiments demonstrate that FRESHPROMPT outperforms other search engine-augmented prompting methods and commercial systems.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study delves into the challenges faced by LLMs in handling dynamically changing information and questions with false premises. The introduced FRESHQA dataset serves as a valuable benchmark to assess the factuality of language models, revealing their limitations and the pressing need for improvement. The proposed FRESHPROMPT method showcases promising results, significantly boosting model performance by incorporating real-time information from search engines. This underscores the potential of in-context learning approaches to enhance language models’ adaptability to evolving knowledge.

Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts

Introduction

Language models have become integral to many modern applications, such as conversational AI, search engines, and document summarization. These models typically process input through long contexts, allowing them to perform tasks that involve large amounts of data, such as analyzing legal documents or processing extensive conversation histories. With advances in hardware and algorithms, context windows have expanded from a few thousand tokens to tens or even hundreds of thousands, enabling the potential for richer understanding and better task performance.

However, a critical question remains: how effectively do these models use their long contexts? While recent models boast extended input capabilities, there’s limited understanding of their performance in scenarios requiring selective retrieval of information embedded in these extended inputs. This blog post explores findings from a recent paper that investigates the ability of language models to handle long contexts effectively. The paper evaluates several state-of-the-art models using tasks such as multi-document question answering and key-value retrieval. Surprisingly, it reveals that models often perform better when relevant information is located at the beginning or end of the input context but struggle significantly with information in the middle.

Research Gap

Despite advancements in language models’ capacity to process long contexts, their ability to effectively retrieve and use information from these extended inputs remains limited. The study identifies several gaps:

- Position Bias: Current models exhibit a “U-shaped” performance curve, favoring information positioned at the beginning (primacy bias) or end (recency bias) of the context, while performing poorly on middle-placed information.

- Extended Context Effectiveness: Models with extended context windows do not necessarily outperform their shorter-context counterparts, indicating that merely increasing the input size doesn’t translate into better performance.

- Task-Specific Challenges: For tasks like multi-document question answering, where models must identify and reason over relevant documents, their inability to uniformly handle all positions in the context limits their utility.

- Architectural Limitations: Decoder-only models, commonly used for LLMs, show significant struggles when dealing with longer sequences, especially compared to encoder-decoder architectures.

- Practical Implications: In real-world scenarios, such as retrieval-augmented applications, the inability to robustly use long contexts may result in inefficiencies and errors, highlighting the need for better evaluation and model design.

This paper’s findings highlight the importance of rethinking how language models process and use long contexts, emphasizing the need for architectures and fine-tuning strategies that address these limitations.

Solution (and Experiments)

The paper proposes a controlled experimental setup to investigate how well language models handle long contexts. Their approach includes the following key elements:

Tasks to Analyze Long-Context Usage

The researchers designed two tasks to systematically evaluate the models’ ability to retrieve and use relevant information from long contexts:

-

Multi-Document Question Answering (QA): Models are given a query and a set of documents, where one document contains the answer and the rest are distractors. The position of the relevant document is varied systematically (beginning, middle, or end of the context) to test how well the models retrieve and reason over the correct information. This mimics real-world tasks like retrieval-augmented generation, where models process retrieved documents to answer questions.

-

Key-Value Retrieval:

A synthetic test designed to minimize linguistic complexity. Models are given a JSON object with randomly generated keys and values and are asked to retrieve the value for a specific key. This task isolates the retrieval mechanism by removing language features as confounders. The position of the key-value pair is similarly varied within the input.

Experimental Variables

To understand the models’ behavior under different conditions, the researchers manipulated:

- Context Length: They varied the number of documents or key-value pairs in the input, increasing the input size to test whether longer contexts affect performance.

- Position of Relevant Information: By altering the placement of the relevant document or key-value pair (beginning, middle, or end), they measured how performance changes based on positional bias.

Models Evaluated

The study tested several state-of-the-art language models, including both open-source and proprietary ones:

- Open Models: MPT-30B-Instruct, LongChat-13B (16K)

- Closed Models: GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-3.5-Turbo (16K), Claude-1.3, Claude-1.3 (100K)

These models represent varying architectural designs and input context sizes, offering a broad view of current capabilities.

Metrics for Evaluation

The researchers used task-specific metrics, such as:

- Accuracy: For both tasks, whether the model correctly retrieved the desired answer or value.

- Closed-Book vs. Oracle Performance: To contextualize results, they compared models’ closed-book accuracy (no context provided) and oracle accuracy (provided with only the relevant information).

Investigation of Contributing Factors

The study also explored why models struggle with middle-context information by analyzing:

- Model Architecture: Comparing decoder-only and encoder-decoder designs.

- Query-Aware Contextualization: Testing whether placing the query both before and after the context improves performance.

- Instruction Fine-Tuning: Evaluating whether fine-tuning affects positional biases and retrieval robustness.

Findings

The study uncovered several key insights into how language models handle long contexts:

- Positional Bias: U-Shaped Performance Curve

- Language models perform best when relevant information is located at the beginning (primacy bias) or end (recency bias) of the input context.

- Performance significantly drops when relevant information appears in the middle of the input, forming a “U-shaped” curve. For example, GPT-3.5-Turbo’s accuracy in the middle-context setting can fall below its closed-book performance.

- Limited Advantage of Extended Context Models

- Models with larger context windows (e.g., GPT-3.5-Turbo 16K and Claude 100K) do not necessarily perform better than their standard counterparts when the input fits within both models’ context sizes.

- Simply increasing the input size capability does not translate into better usage of long contexts.

- Task-Specific Challenges

- In multi-document question answering, models struggle to retrieve and reason over relevant documents when the answer is embedded in the middle of the context. This occurs even when only one document contains the correct answer.

- In key-value retrieval, some models, like Claude, perform perfectly, but others exhibit the same U-shaped performance trend as in the QA task.

- Architectural Observations

- Decoder-only models (e.g., GPT-3.5, MPT-30B) exhibit stronger positional biases than encoder-decoder models (e.g., Flan-T5-XXL, Flan-UL2). Encoder-decoder models process context more robustly but still struggle when input lengths exceed their training-time limits.

- Instruction fine-tuning slightly mitigates biases but does not eliminate them, especially for larger models.

- Practical Implications

- For retrieval-augmented tasks (e.g., open-domain QA), increasing the number of retrieved documents provides diminishing returns. Models struggle to use additional documents effectively, even when they contain relevant information.

- Effective document ranking and truncation strategies could improve performance by placing relevant information near the beginning or end of the input.

- Query-Aware Contextualization

- Placing the query both before and after the input context significantly improves performance in simple tasks like key-value retrieval.

- However, this strategy has limited impact on more complex tasks like multi-document question answering.

- Scaling and Model Size

- The U-shaped positional bias becomes more pronounced in larger models (e.g., 13B and 70B parameters). Smaller models tend to exhibit primarily recency bias.

- Scaling models and fine-tuning with human feedback reduce, but do not completely resolve, positional biases.

Conclusion

These findings reveal that current language models do not robustly utilize long input contexts. Positional biases and inefficiencies in reasoning over middle-context information present significant limitations, even in extended-context models. These insights underscore the need for architectural improvements and better training strategies to fully leverage long-context capabilities.