Paper Review - Week 9

To me, the most interesting papers among those published in this week are:

- Reward Design with Language Models

- MathPrompter: Mathematical Reasoning Using Large Langugage Models

- LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models

Reward Design with Language Models

Introduction

This paper introduces a novel approach to reward function design in Reinforcement Learning (RL) by leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT-3. Traditional methods of designing reward functions involve either manually crafting complex functions or collecting extensive labeled data, both of which can be challenging and impractical. The authors propose using LLMs as proxy reward functions, allowing users to specify desired behaviors through natural language prompts. By evaluating the agent’s behavior against these user-specified objectives, the LLM provides textual feedback that is converted into numerical rewards for training the RL agent. This approach aims to simplify the reward design process, making it more intuitive and efficient, and to improve the alignment of RL agent behavior with user objectives.

Research Gap

Designing effective reward functions is a critical and challenging aspect of RL. Traditional approaches to reward design often involve manually crafting reward functions or collecting large amounts of labeled data to train supervised models. These methods have several difficulties: they require deep domain knowledge, are susceptible to reward hacking, and do not generalize well to new tasks or user preferences. Moreover, creating reward functions that balance multiple objectives is notoriously complex, and the extensive data requirements for supervised learning models make this process costly and time-consuming. This paper addresses these significant gaps by proposing an innovative method that leverages LLMs such as GPT-3 as proxy reward functions.

Advantages of the Proposed Method:

-

Simplified Reward Design: The use of natural language prompts allows users to specify desired behaviors in an intuitive and accessible manner. This removes the need for expert-level knowledge in crafting complex reward functions.

-

Data Efficiency: The LLM-based approach demonstrates superior data efficiency by requiring only a few examples (few-shot prompting) or even zero examples (zero-shot prompting) to generate effective reward signals. This significantly reduces the cost and effort associated with collecting extensive labeled data.

-

Flexibility and Generalization: LLMs are pre-trained on vast amounts of internet-scale text data, enabling them to generalize well across different tasks and user objectives. This flexibility allows for broader applicability and adaptability to new environments without needing to redesign reward functions or collect new data.

-

Mitigation of Reward Hacking: By leveraging the extensive pre-trained knowledge of LLMs, the approach can provide more accurate and contextually appropriate reward signals, reducing the likelihood of reward hacking where agents exploit poorly designed reward functions.

-

Improved Alignment with User Objectives: The LLM-based method has shown to better align RL agent behavior with user-specified objectives compared to traditional supervised learning models. This results in RL agents that perform more in line with the nuanced preferences of users.

-

Robust Evaluation and Performance: Experimental results across diverse tasks, such as the Ultimatum Game, Matrix Games, and the DEALORNODEAL negotiation task, demonstrate the effectiveness of the LLM-based approach in providing high labeling accuracy and better RL agent performance.

Solution

This paper explores an innovative approach to designing reward functions for training RL agents. This method leverages LLMs like GPT-3 to simplify the reward design process, making it more intuitive and efficient. Here’s a detailed summary of their method:

- Objective Specification via Prompts:

- Users specify the desired behavior of the RL agent through natural language prompts. These can include a few examples of the behavior (few-shot prompting) or a description of the behavior (zero-shot prompting).

- Role of the LLM:

- The LLM acts as a proxy reward function. It evaluates the agent’s behavior against the user’s objectives, expressed in natural language, and provides a textual evaluation (e.g., yes/no or a score).

- The LLM’s evaluation is converted into a numerical reward signal using handcrafted parsers, which is then used to train the RL agent.

- Training Phase:

- The RL agent generates behaviors by interacting with the environment.

- The LLM evaluates these behaviors based on the user-specified objectives and provides corresponding reward signals.

- The RL agent updates its policy using these reward signals, iteratively refining its behavior to align with the user’s objectives.

- Inference Phase:

- Once the RL agent is trained, it uses the learned policy to operate independently in the environment without further input from the LLM.

- The LLM is not involved in the inference phase; the RL agent acts autonomously based on its training.

- Evaluation and Baselines:

- The effectiveness of the LLM-based reward design is evaluated against traditional approaches:

- Supervised Learning (SL) Baseline: A supervised learning model is trained on labeled examples to predict rewards. The LLM is used to generate these examples in a few-shot setting. This SL model then predicts reward signals for the RL agent based on these examples.

- No Objective Baseline: Uses the LLM without specific user objectives to see how well it generalizes.

- Ground Truth Reward Functions: Uses predefined, ideal reward functions directly encoding user objectives as a benchmark.

- Performance metrics include labeling accuracy (how well the reward signals match ground truth) and RL agent accuracy (how well the agent’s behavior aligns with user objectives).

- The effectiveness of the LLM-based reward design is evaluated against traditional approaches:

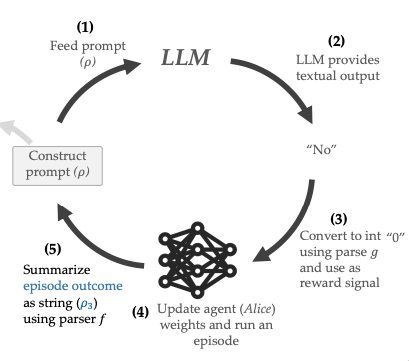

Their proposed solution for training the RL agent is also depicted in this figure:

Experiments

They evaluate the effectiveness of LLM-based reward design through a series of experiments across different tasks. Here’s a summary of the tasks used, a brief explanation of each, and the performance of the models in each task:

- Ultimatum Game:

- Description: The Ultimatum Game involves two players, a Proposer and a Responder. The Proposer suggests a split of a sum of money, and the Responder can either accept or reject it. If the Responder accepts, both players get the proposed amounts; if rejected, both get nothing.

- Objective: Train an RL agent (Responder) to align with user-specified preferences for accepting or rejecting proposals.

- Results:

- Labeling Accuracy: The LLM-based approach maintained high labeling accuracy with both 10 examples and a single example with an explanation.

- RL Agent Accuracy: The RL agents trained with LLM-generated rewards showed higher accuracy in aligning with user preferences compared to those trained with the SL baseline.

- Matrix Games:

- Description: This task involves two-player normal-form games like Battle of the Sexes, Stag Hunt, Chicken, and Prisoner’s Dilemma. Each game consists of a single timestep with discrete actions leading to joint outcomes and rewards.

- Objective: Evaluate the ability of the LLM to provide reward signals based on well-known solution concepts like total welfare, equality, Rawlsian fairness, and Pareto-optimality.

- Results:

- Labeling Accuracy: The LLM-based approach significantly improved labeling accuracy over the No Objective baseline, particularly when using zero-shot prompting.

- RL Agent Accuracy: RL agents trained with LLM-generated rewards achieved high accuracy in meeting the objectives, often outperforming the No Objective baseline.

- DEALORNODEAL Negotiation Task:

- Description: This long-horizon task involves a negotiation between two agents, Alice and Bob, over the allocation of a set of objects (books, hats, and balls). The agents propose and counter-propose allocations until an agreement is reached or the negotiation fails.

- Objective: Train Alice to negotiate in styles specified by the user, such as versatile, push-over, competitive, and stubborn behaviors.

- Results:

- Labeling Accuracy: The LLM-based approach generally outperformed the SL baseline, especially for styles like competitive and stubborn.

- RL Agent Accuracy: RL agents trained with LLM-generated rewards better aligned with user-specified negotiation styles compared to those trained with SL. A pilot user study also confirmed that users rated LLM-trained agents as more aligned with their preferred styles.

Overall Performance

- Labeling Accuracy: The LLM-based reward design consistently showed high labeling accuracy, indicating that the LLM could effectively generate reward signals aligned with user objectives.

- RL Agent Accuracy: RL agents trained with LLM-generated rewards performed better in aligning their behavior with user objectives across all tasks compared to traditional baselines.

- Data Efficiency: The LLM-based approach demonstrated superior data efficiency, achieving high performance with fewer examples compared to supervised learning models.

- Flexibility and Robustness: The approach generalized well across different tasks and objectives, showcasing the flexibility and robustness of using LLMs for reward design.

Conclusion

The experimental results demonstrate that the LLM-based reward design significantly outperforms traditional approaches in various tasks, including the Ultimatum Game, Matrix Games, and the DEALORNODEAL negotiation task. The LLM-based method showed higher labeling accuracy and better alignment of RL agent behavior with user objectives, while also proving to be more data-efficient. Additionally, the method exhibited robust generalization across different tasks and objectives. Overall, the study highlights the potential of using LLMs to streamline and enhance reward design in RL, providing a flexible and effective solution for training objective-aligned agents.

MathPrompter

This paper focuses on using LLMs for mathematical reasoning. Some of the challenges in this work are as follows:

- Mathematical operations usually have a single correct answer.

- Not only the final output is important, the procedure and the intermidate steps that resulted into that final output should also be correct.

- It is difficult to ensure that the generated output and the intermediate steps are all correct. In other words, it is better to have a metric to show that how much the model is confident about the generated output!

Accordingly, MathPrompter tries to propose a solution to increase the validity and reliability of mathematical reasoning using LLMs. Their solution is to simulate the usual approach that studnets usually take for solving a math problem. So, the steps in MathPrompter is as follows:

- Receiving the definition of a mathematical problem as text. For example:

At a restaurant, each adult meal costs $5 and kids eat free. If a group of 15 people came in and 8 were kids, how much would it cost for the group to eat? - Generating a template for the input question and creating a list of values for solving the template:

Template = At a restaurant, each adult meal costs A and kids eat free. if a group of B people came in and C were kids, how much would it cost for the group to eat? Mapping = {A:5, B:15, C:8} - Creaing proper prompts for creating different solutions. For example, one solution can be a python function and the other can be a algebraic equation. So, by providing these prompts to the LLM:

Algebraic prompt: Write a mathematical equation and generate the answer format starting with ‘Answer =’ Python prompt: Write a Python function that returns the answer.then, the LLM is supposed to generated the two following outputs:

# Algebraic expression output Answer = A * (B - C) # Python expression output def total_price(A, B, C): return A * (B - C)These outputs can help the user to have an insight about how the LLM is reasoning.

- Then, MathPrompter uses different randomized values for \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\). Then, it passes all the randomized values to the both outpus. If, for more than 5 times, the result of the two outputs (algebraic and python expression) are the same, then both of them are accepted as the correct solutions for the mathematical problem.

This is definitely a very interesting and novel idea. However, I personally have some concerns about it:

- First of all, MathPrompter is not making it easier for LLMs to find a solution. The only thing that it does is to ask LLMs to generate multiple outputs, such as algebraic and python expression.

- MathPrompter uses several randomized values (at least 5 values) to validate if the LLM outputs result in the same number or not. However, it is not clear that how these randomized values are generated. If users are supposed to provide these values, then I think it somehow makes the LLM useless here! Because users need to solve the problem themselves to be able to provide such values. So, in this case, they don’t need LLMs anymore! :)

- If for the specific values in the input mathematical problem, algebraic and python expressions result in different values, then what can be reported to the user?

LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models

Recently, the trend of novel language models is that they are becomming larger and larger. The main idea behind this trend is that, probabely, by increasing the number of parameters of a language model, it can have a better performance. In other words, the prevalent idea is that, the larger the model, the better the performance.

However, a paper, published in 2022, tried to challange this idea. They hypothesised that it is not only the size of the language models which make their quality better. There is another very important aspect: the size of the training data. This hypothesis, which is also known as the Hoffmann’s Scaling Law, has been the foundation of one of the recenly-proposed language models, named Chinchilla. Chinchilla has only 70B parameter (compared to GPT-3 with about 175B parameter) and can still get comparable performance to GPT-3.

LLaMa is another novel language model which uses the Hoffmann’s scaling law as its foundation. It has several variants, each of which with different number of parameter–ranging from 7B to 65B parameter. Although the size of the model is significantly smaller than GPT-3, it has comparable results to GPT-3 for most downstream task; and even for some of the downstream tasks, it can outperform GPT-3.

Now, to investigate the specific charactristics of LLaMa, we look at its three aspects:

- Training Datasets

- Architecture

- Performance

Training Datasets

As mentioned previously, LLaMa is supposed to have between 7B and 65B parameters. To this end, according to the Hoffmann’s scaling law, the training dataset consist of 14 Trillion tokens. To collect this 14 Trillion tokens, the following datasets are used:

- English CommonCrawl [67%]: Public crawled web pages from 2017 to 2020

- C4 [15%]: Preprocessed CommonCrawl!

- Github [4.5%]

- Wikipedia [4.5%]: Covering 20 languages from June 2022 to August 2022

- Gutenberg and Books3 [4.5%]: Two book corpora from public domain

- ArXiv [2.5%]

- Stack Exchange [2%]: From 28 topics

Architecture

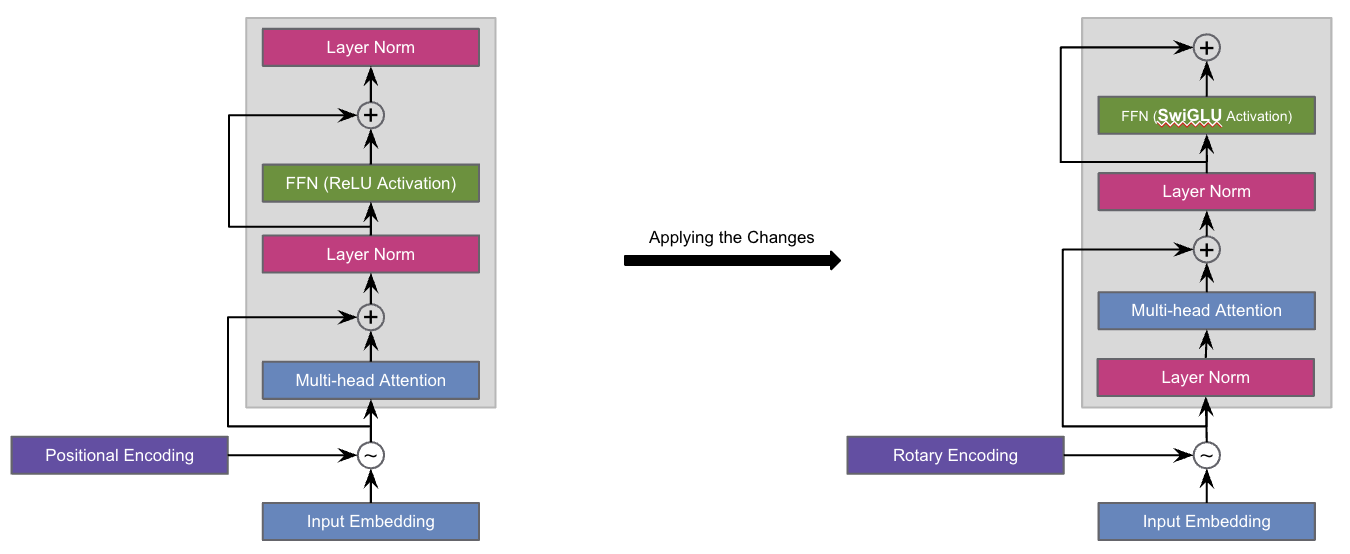

LLaMa is a transformer-based model. However, instead of using the main transformer building block as it is, they apply several minor changes to it. These changes are mainly for reducing the training time. The changes are as follows:

- Pre-normalization instead of post-normalization

- Activation function from ReLU to SwiGLU

- Positional encoding from absolute to Rotary

The following image represents how the architecture looks like after applying the above changes. The image on the left shows the usual transformer building block and the one on the right illustrates the building block after applying the changes.

Performance

They have evaluated LLaMa on different tasks and compared it with the two of the recent extremely large language models. The results are as the following:

- Common Sense Reading

- Evaluated in zero-shot setting.

- LLaMa (65B) outperforms Chinchilla (70B).

- LLaMa (65B) outperforms PaLM (540B) and GPT-3 (175B) on most datasets.

- Closed-book Question Answering

- Evaluated in zero-shot and few-shot settings.

- LLaMa (13B) is competitive with GPT-3 (175B) and Chinchilla (70B).

- LLaMa (65B) outperforms PaLM (540B), GPT-3 (175B), and Chinchilla (70B).

- Reading Comprehension

- Evaluated in zero-shot setting.

- LLaMa (65B) is competitive with PaLM (540B).

- LLaMa (13B) outperforms GPT-3 (175B).

- Mathematical Reasoning

- LLaMa (65B) outperforms PaLM (540B).

Here are some more articles relevant to this one: